Basics of Game Narrative

Alright, here’s a fun one. Today we’ll be going over the fundamentals of game narrative and the different styles and techniques used to tell engaging stories. Here’s our list of topics for today:

Types of Narratives

Linear, Foldback (and variables), Open

Whilst I would find it shocking if a reader of this article has not comprehended the types of narratives used in video games, I will still briefly summarize all of the major forms. This is both to ensure everyone has an equal understanding of the topic and so that it is easier to build off of for other points.

Linear Narrative

Linear narratives are games that bring the player from point A, through point B, to point C. Not much must be explained here. Most older games and many indie short titles are linear based. The trick to linear games is to continue to give the consumer a sense of agency even though the entire story is pre-scripted. How to do this will be touched upon later.

Branching Narratives

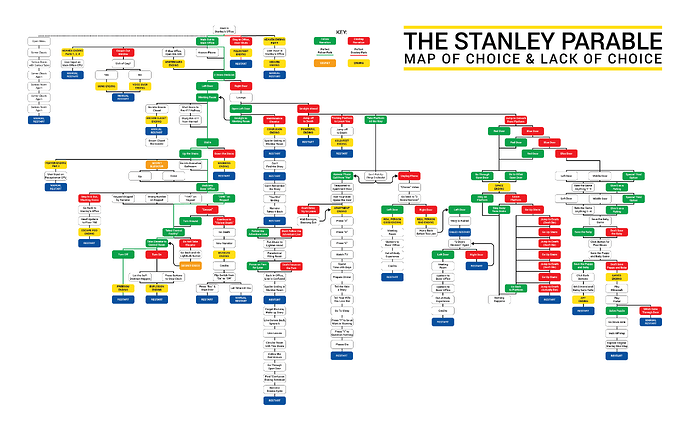

Branching narratives are the first form of nonlinear gameplay. Rather than rely upon a set, pre-determined story, branching narratives grant players agency by allowing them to determine how the story unfolds. This has several advantages, primarily greater player agency than a linear narrative while still giving the game an intentional story.

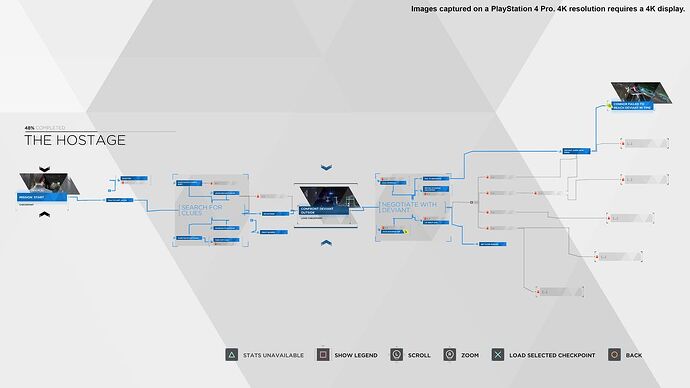

Foldbacks are an integral part of many branching narrative games. A foldback is where the numerous branching paths reconvene at a key focal point. For example, in Detroit: Become Human’s Hostage Rescue Mission, the player is free to do whatever he wants, whether that be saving the fish that fell out of the tank or grabbing the gun that slid under the table. No matter what decisions are made, however, the player will always have two events happen: They will always speak to the police captain and they will always go outside to negotiate with the hostage taker. The decisions made in between are critical and drastically effect the storyline, but the character’s actions will always fold back into key moments.

Nearly every game with a branching narrative operates with some foldbacks, and all must design particular scenes and paths to choose from. When creating game branching paths, one would be wise to consider The Game Narrative Toolbox’s three tips:

“When offering players a large choice that will increase the scope for you and the team, you get the most bang for your buck by ensuring:

- The choice is telegraphed clearly during the buildup, so players are excited to make the choice.

- Players have some idea what the consequences of their decision will be before they make it.

- Ramifications from the decision are seen both immediately (within the next thirty minutes after making the choice) and at the end of the game. These are the two times in which your callbacks will have the most emotional resonance.”

IF AT ALL POSSIBLE, PLAY THESE TWO GAMES. Both have free demos, so as long as you have any form of operational computer, you should be able to at least taste the beauty of these two games. I strongly recommend that you do absolutely no research about these games at any point. Experience them for yourself. It will blow your mind open to so many concepts involving narrative and how gameplay is designed.

The Stanley Parable

Detroit: Become Human

Open Worlds

Open-world games are among the most popular genres currently. What makes these titles both the most engaging and among the most difficult to create well is their sandbox nature. Rather than curate and craft a captivating experience for your players, you must create ingredients and loose encounters that are then simultaneously randomly fed to and hand-picked by the player. Even open-world games with linear stories such as Skyrim and Valheim are engulfed with random encounters and unique scenarios every playthrough, simply due to how many unscripted and randomized events could occur.

The level of scriptedness and flavor of open-worlds can vary widely. Some games, such as Breath of the Wild, have hand-crafted encounters that gives the player exactly the feel the developers wanted them to. On the other hand, Skyrim has thousands of encounters that play out drastically different depending on how you have played up to that point.

So much, then, for the forms of narrative storytelling.

Tensions, Climaxes, and Resolutions

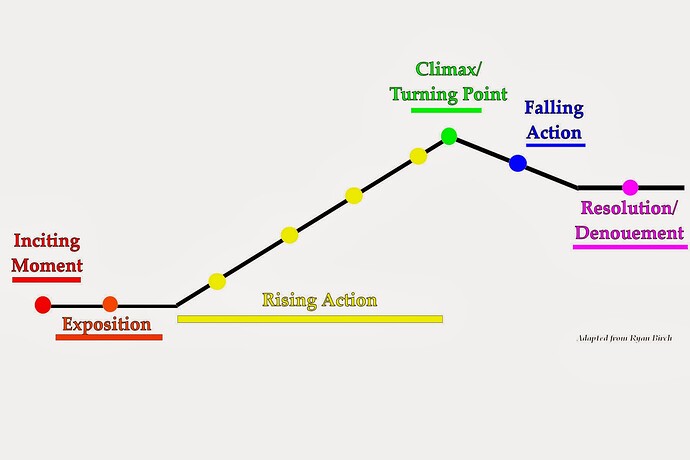

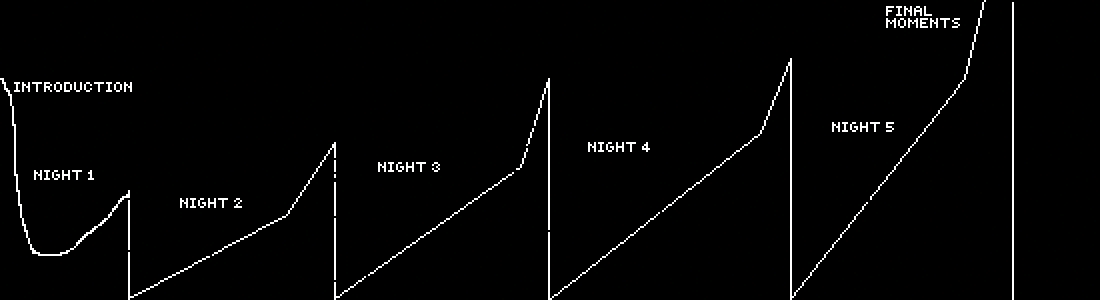

Designing tensions, climaxes, and resolutions in your game takes intentional design. First, before you create your game, it is highly recommended that you make a story chart.

The standard story arc in most narrative art follows this basic trend. If you didn’t see this in third grade, I am unsure of what planet you came from. However, I will quickly explain how this works application to games.

First off, exposition and building the world’s settings is often a pitfall for beginning game developers. In the introduction to the game, you must give the player the rules of engagement in the game. For example, if the setting is a 1920’s noir game but with magic, you must explain to the player that there is magic in the introduction. Otherwise, content can often fly out of left field and feel both immersion breaking and poorly written. Take a look at Hogwarts Legacy’s fantastic introduction:

For most stories, rising action takes the bulk of the story. In Papers, Please, the border tension and difficulty in keeping your family slowly escalates till it comes to a climactic release. In Skyrim, the consequences of failure begins at personal loss to losing your life to an entire city being decimated to the potential obliteration of mankind. The rising tension often, but does not always, include a rise in gameplay difficulty. It Takes Two does not scale difficulty, unfortunately to its own demise. As the enchanted couple get closer and closer to their goal of returning to their human bodies, the characters get more and more thrilled… and you do not. Rather than building mechanics upon each other, whenever a new mechanic is introduced, the old one is thrown out.

(You needn’t watch the entirety of the bossfight, but witness how the second boss in the game is nearly identical in difficulty and complexity to a late-game boss.)

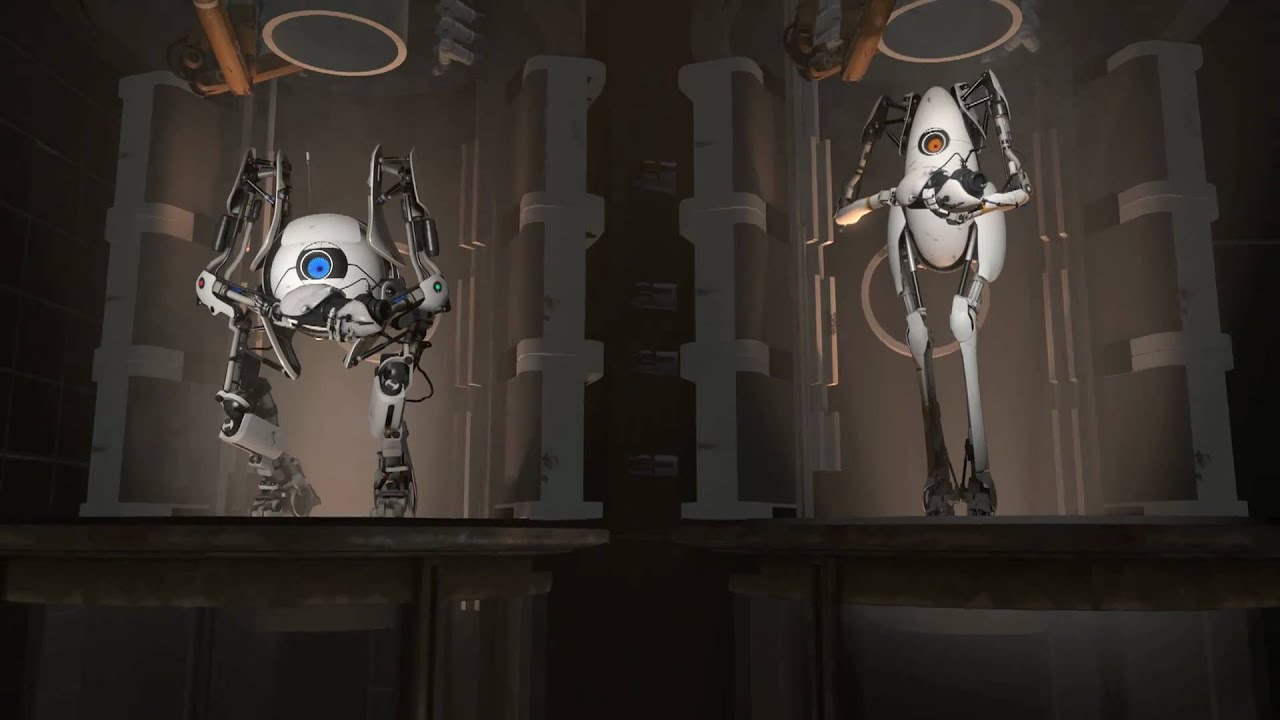

So many mechanics that have an incredible amount of potential are simply thrown out after one use. This severely hinders the depth of gameplay and engagement. Portal 2 takes a similar approach, but rather than become another infamous AAA title, it is widely regarded as a witty and engaging masterpiece. What makes Portal 2 different?

For starters, although difficulty is not changing, the baseline difficulty of the game is consistently higher than It Takes Two. This allows the entire game to be more engaging than the former example. Additionally, Portal 2 fleshes out its concepts. There is no weak point to the game, as all of the simple mechanics are explored so thoroughly that the player simply must try with all his or her might to keep up with the developers’ creativity. As this is the case. In as simple of terms as possible, while It Takes Two attempts to add new game to new game, Portal 2 redefines itself every single level, leaving players guessing what will be the next big twist on its original concept.

Designing narrative tension is easy to learn but hard to master. Often, in games such as Five Nights at Freddy’s, the game’s narrative tension is directly correlated to the tension of the gameplay. As with many horror games, the two strongest jumps in narrative tension are the introduction and the conclusion. In order to derive the strongest emotions in a player, you must either give them relatable characters and/or situations, or you must completely engross them in gameplay. This makes every moment count as a thrilling memory.

For example, in Five Nights at Freddy’s, the beginning is meant to feel immersive, as both the character and player are completely ignorant of what is occurring. This gives significant relatability and, as the situation you find yourself in is less than desirable, a unique fear of the unknown emerges. As the player shifts from emotional stimulation to mental stimulation, the game consistently ups its fear, once again immersing the player in the moment. This shifts the fear of the unknown to the fear of failure, which only consistently increases as tensions rise.

Keeping narrative tension is an ever-present problem that constantly requires a creative solution. Fortunately for us, this also means there are many examples for us to study.

In EA’s masterpiece PVP title Battlefield 1, an interesting narrative tension technique is implemented. Narrative tension is nearly impossible to withhold in an online game, as player interactions are nearly impossible to predict. However, rather than narrate a specific character, the Battlefield narrative is given per-army. An initial combat scenario is given, and if one side wins that battle, they will advance to the next frontier, thereby pushing the opposing army into a defensive gamemode next round. However, if one side is nearing a defeat, the game will implement a cutscene and grant the losers a final hail-mary strike with a Behemoth. This is excellent design, as it prevents one side from losing hope of a victory.

A brilliant example of how to hold narrative tension in an open-world game is Project Zomboid. I have mentioned this game briefly in my previous article, and it is discussed for good reason. From the beginning of the game to the very last breaths your survivor takes, the world is constantly finding new ways to surprise and end you. The first few days of your survival is all about surviving in the shadows.

You are forced to flee from hordes of undead, as you have few resources to be creative with and your character isn’t a god: he needs a break often. During this time, you have to consistently manage hunger, health, water, boredom, stress, and panic meticulously. Once you get yourself situated and begin to master managing these effects, an entire new wave of issues besets you. That hammer that kept you alive for so long? It’s not invincible, find a way to repair it. You took a risk and ate that soup on the counter? You have a stomach bug now, stay alive. You took a fall? There’s a deep laceration, find medical equipment to stitch it up or it won’t heal properly.

Presuming you manage to survive long enough, the game hurls another tidal wave of hurdles upon you. You managed to forage and sneak in the shadows well, but now the power is off and all the food you find will be rotten. How are you going to eat? You made a garden, lovely, but where are you going to get water for it? You made rain collectors, wonderful. How are you going to purify the water? As the intricate systems of Project Zomboid are so dynamic and in-depth, the challenges that arise from them are equally as diverse. Old challenges are not casually thrown away, but rather left for the player to master and feel rewarded out of. What is most fascinating of all, however, is the narrative tension throughout the playthroughs. As a rogue-lite, your knowledge and skill increases in every playthrough, thereby creating an infinitely increasing tension as you survive for longer and longer. Every death is just a down in the narrative and every day you live longer is one more hurdle to overcome.

Some games, such as Undertale, keep the mood of the game separate from the difficulty, whereas others, such as Little Nightmares, keep the dramatic tension of the story the center of attention for the entirety of the gameplay. There is no right way to do narrative tension. Like all parts of the storytelling arts, it is best to learn why tropes and trends, such as a narrative slope, is so impactful before deviating form them.

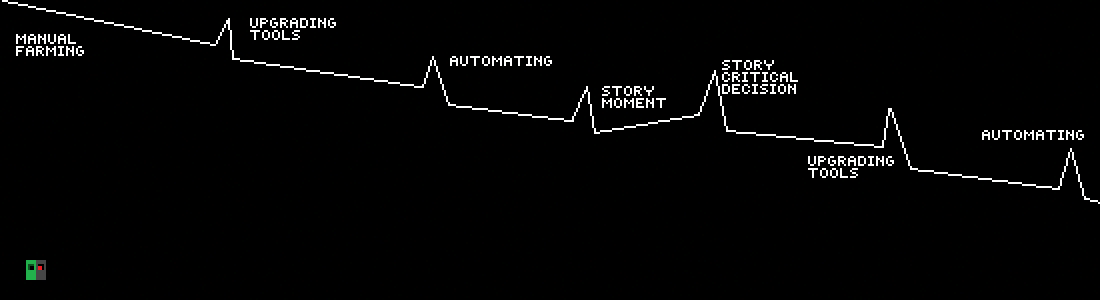

There are many exceptions to these rules, two being stark examples. Stardew Valley has a fascinating tension chart, as it actively attempts to release you from your strenuous tasks as you progress. Rather than increasing in difficulty, the game decreases and nearly (but not quite) devolves into a tycoon game. As you acquire better tools and craft more profitable and less manual-labor intense things, your gameplay slows down, allowing you to do the things you enjoy and desire to do for fun, such as play the arcade machines, become close friends with the community members, and fish for rare specimens. This is an intriguing trend, as the game actively encourages you to make the difficulty more lax. Excitement arises at new spectacles that allow you to free more of your time until you have as much free time as your heart desires.

Pokémon has a roughly similar strategy with intriguingly different results. Rather than beginning at an intensive level, Pokémon games for the most part continue at an equal level of difficulty. The game never requires you to get better or to try something new or to solve a new mystery. In sync with its linear gameplay mechanics, the flow of the game continues at a basic pace of:

- Find a new Pokémon / evolve your Pokémon

- Upgrade your Pokémon

- Battle until you level up

- Get the Gym Badge

- Rinse and repeat

Due to this lack of skill requirement or narrative tension, the player is less inclined to engage with the story and core gameplay mechanics. Rather, there are several other reasons to play. Some enjoy the Pokémon franchise due to this lax nature and use it as a relaxing experience rather than a challenging game. One of the main selling points, however, is its unique bestiary which caters to male and female players, primarily of a younger age range. This also brings in a solid excuse for its sorely lacking difficulty in gameplay, as Pokémon is many children’s first experience with a video game. One should not be so quick to critique Pokémon, as it is the highest grossing multimedia franchise in the world. Clearly, they did something right. Finally, some players enjoy the experience of optimizing and the quick reward of strategic evolution and levelling decisions. For example, most novice players will quickly discard a Magikarp, while experienced players can choose to take the added difficulty of playing with an extremely weak Pokémon for future profit. Of course, all of this challenge matters little, as you can easily beat the game without a second thought and no additional adventures pursued, but the emotion you give players from their intentional critical thinking is what is really sold well here.

Personal note: if you would like to try a fairly decent Pokémon game, my personal favorite is Pokémon Emerald. Give it a shot if you have the time, even if you have never touched the franchise. You might enjoy yourself more than you expected. I sure did!

Finally, if you have the time, please watch this excellent short video essay on how the Mario franchise dynamically changes the tension and difficulty real-time:

Magic Circles

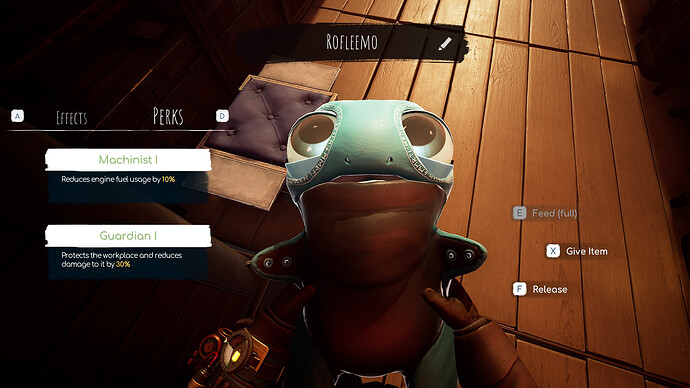

Magic Circles are an integral concept that should be added to your vocabulary if you desire to pursue any narrative storytelling design in the future. Put as simply as possible, a magic circle is the new set of rules that the world you are creating is run by in place of the confines of actual reality. For example, in Voidtrain, your understanding of the common laws of physics and science are replaced by the fantastical steampunk world of space nazis and adorable six-legged Rofleemos.

Two serious pitfalls come into play when creating your magic circle: real-world comparison and consistency. Consistency is often the most major issue, so let us discuss this first.

In Resident Evil: Village, it is established early in the game that First Aid Meds can heal all sorts of injuries, from gaping holes in your torso to gunshot wounds. Even then, however, the scene in which the protagonist “glues” his severed hand back on is pushing the limits and was not entirely well-received by critics. Even though this concept had been theoretically established beforehand, the outlandishness of it all in relation to real-world scenarios and what is has been seen used for before makes this pushing the limits of the magic circle set for the world. However, imagine how much worse this scene would be if outstanding injuries were not healed beforehand! Giving clear definitions to any fictional logic in your world will do wonders to increase immersion and the effectiveness of your story.

Some narratives break their magic circle consistently, such as the new Star Wars films. This has been the biggest gripe of many a dedicated fan, as established facts were utterly discarded in favor of a potentially dramatic reveal. This both decimated fans’ trust in the series as well as severely reduced the emotional captivation of the intended revelations. For example, it was canonically established that only Sith, EXTREMELY powerful Sith, can conjure force lightning. When Rey spontaneously acquires this new ability without even a pathetic attempt at explaining the plot holes, the immersion of the story falls apart.

Magic circles are intended to replace real-world boundaries. As such, it is dangerous to create a magic circle that overlaps with reality without doing the proper research. For example, I am a dungeon master for a homebrewed Pathfinders campaign. As I am creating the world, I must be extremely intentional with how I create the story, as every opportunity I deny the players due to a lack of narrative consistency is a missed opportunity for a fantastically creative moment. As there are lunar events in my campaign, I had to create a predictable orbit of the moon. Because the moon must be predictable, there must be a calendar. As the calendar must be applicable, I had to create seasons, tides, lunar cycles, and even a rough outline of the solar system so that the party can use every piece of the world to their advantage. If I were to not create my own calendar, or even worse, create a calendar but not inform the players that it exists, they would assume that all of the aforementioned subjects work as the real world does. This could cause significant issues in the story as a whole as well as ruin creative plans (such as “Let’s hold off on attacking the Werewolf tonight because it will be a full moon”).Such research and worldbuilding can be applied to everything from local taverns to basic adventuring. If something is canonically (or potentially canonically) a variation from real-world guidelines, it is absolutely essential that this be spelled out before it becomes applicable to the narrative. This is painted to perfection in the Sherlock Holmes book series (and BBC television adaptation), as every minute detail is researched thoroughly enough to reward a perceptive and well-informed reader with essential clues.

This about summarizes the basics in narrative design. There is so, so much more I desperately desired to write about, but alas, I am at my eleventh page of writing and most certainly my Gen Z readers have dozed off. I would love to have discussed creating side quests, intentional breaking of magic circles, and how to make decisions feel real and meaningful, but I will save those all for a future endeavour. I even held off on analyzing one of the best plots in media history, that of Inscryption, both due to severe spoiler issues and word count. Instead, I will make a clear, short list of titles and videos you MUST experience if at all possible. I implore you, if you have any spare time whatsoever, please, please go through this list. They are some of the objectively best narrative experiences that are on the market today. Thank you for reading, and as always I am completely open to feedback, new opinions, and critiques. I look forward to writing the next article!

MUST HAVE experiences

BBC’s Sherlock – It’s Sherlock. You literally can’t get better than this.

Inscryption – This is the best video game of all time, in my opinion. do NOT spoil it for yourself!!!

Detroit: Become Human – Potentially some of the most timeless and perfected branching narrative in gaming history.

The Stanley Parable – the end is never the end is never the end is never the end is never

Further reading

Shadiversity – for all things medieval and fantasy

Game Maker’s Toolkit – a wonderful resource for finding game design concepts. Mildly politicized but overall ignorable.

Indie Games: The Complete Introduction to Indie Gaming – a thorough and light read for those who wish to seriously study. I recommend this as pre-college preparation for anyone going into game design as an occupation.

![Overwatch 2 All Weapons Showcase [PC STEAM 2023]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/WHKBInv7eJg/maxresdefault.jpg)